|

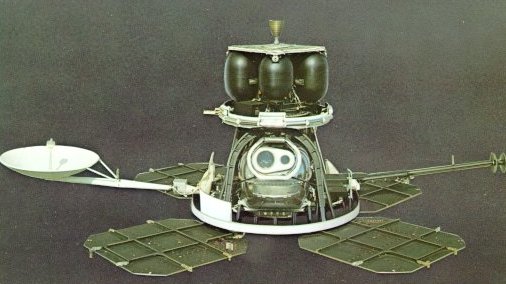

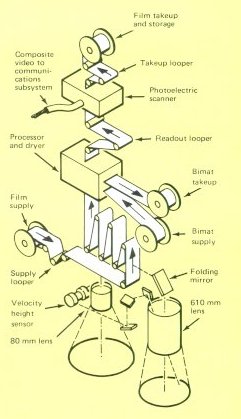

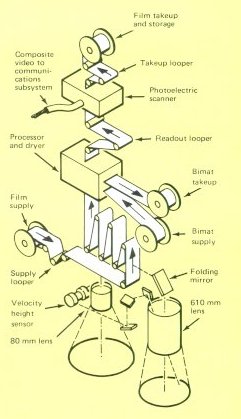

It was in its photo system that Orbiter was most unconventional.

Other spacecraft took TV images and sent them back to Earth as

electrical signals. Orbiter took photographs, developed them on

board, and then scanned them with a special photoelectric system - a method

that, for all its complications and limitations, could produce

images of exceptional quality. One Orbiter camera could

resolve details as small as 3 feet from an altitude of 30 nautical

miles. A sample complication exacted by this performance: because

slow film had to be used (because of risk of radiation fogging),

slow shutter speeds were also needed. This meant that, to prevent

blurring from spacecraft motion, a velocity-height sensor had to

insure that the film was moved a tiny, precise, and compensatory

amount during the instant of exposure.

|